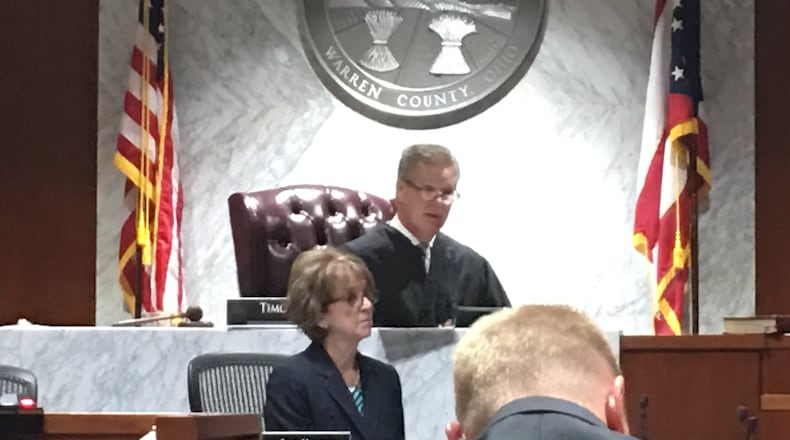

The bailiff in Judge Tim Tepe’s courtroom walked to the jury box, passed out cards, and jurors wrote down questions they wanted the witness to answer. After the questions were collected, both sides conferred with the judge. Then Tepe read the jury questions that he ruled were appropriate.

It’s a rare practice in Ohio — but not unheard of — to permit jurors to question witnesses, a decision up to the judge.

For now, Tepe is the only area judge letting the jury have a more vested role in the process with questioning. A 2020 survey by the Ohio Jury Management Association indicated only 26 out of 95 judges responding permitted jurors to ask questions of witnesses.

Tepe, who was elected and took the bench in 2017 after practicing law for 31 years, began considering the practice several years into his judgeship.

After hearing the idea from a judge in northern Ohio, Tepe adopted the policy in the fall of 2019.

“It fascinated me because as a practicing attorney, when you do a jury trial, it is always something that you don’t know what the jury is thinking until after the trial when you talk to them after their verdict,” Tepe said.

“I always thought it would be interesting to know, because you know attorneys always think they can read juries, what they are thinking and what their angle is during the course of the trial. Because attorneys get locked in on their theory of a case and are pursuing a certain angle, then when the jurors ask questions, they realize they need something else explained.”

But those juror questions are vetted, and they must follow the same rules of law as those asked by attorneys.

“I had to develop it in a way that I felt protected everyone’s rights,” he said.

There is no identification about which juror penned the question, and there are many cases in which questions are not asked because they do not follow the rules of evidence, such as introducing hearsay testimony.

Tepe noted his judgeship did not begin with the practice, but he thought about it for a while. He was struck by his own questioning of witnesses during bench trials, when he was the sole finder of fact.

“When I am the trier of the facts, I ask questions because I want to get to the truth,” he said. “Well, the jurors are the triers of fact, and if they have questions or something is not being asked or answered, they too should have a chance to ask questions and find out the information needed to get to the truth.”

Warren County Prosecutor David Fornshell said he talked with Tepe before the new policy was established.

“I said ‘I don’t like it,” Fornshell said with a chuckle, adding he understands the reasoning behind the decision.

“The arguable benefit of it is that prior to closing arguments it may give you some insight into what a juror is thinking or wondering with respect to a witnesses’ testimony or the case itself.

“The jurors sit there and listen to lawyers go back in and forth and back and forth during questioning and sometimes think, ‘Well, dummy, this the question I want answered.’”

The same practice isn’t used in Butler County, where attorneys ask all the questions, said longtime Butler County Common Pleas Judge Noah Powers II.

Powers said the practice of jurors questioning witnesses is fraught with pitfalls.

“It’s hard to un-ring a bell if a juror asks a wrong question, and the answer that gets out can result in a mistrial. Lawyers understand the rules of evidence, and even they make mistakes and we have mistrials,” Powers said.

Butler County Prosecutor Michael Gmoser said he is also not a fan of jury questions. He said it adds a level of complication to an already complicated legal process.

“It is inviting an intrusion in the process that makes it more of a hodgepodge of questions, and there is a giveaway as to what the jurors are thinking to both sides,” Gmoser said.

He added if the jury doesn’t get all their questions answered, “then that’s reasonable doubt.”

Frank Schiavone III, who has been practicing law since 1978, said the jury questioning of witnesses did happen once in Butler County in the late 1980s or 1990 in Butler County Common Pleas Judge Anthony Valen’s courtroom. He was the defense attorney and lost, but the case was overturned on appeal and the defendant was given a new trial.

“Traditionally it has not been done, and the trial practice is filled with tradition,” he said. “The part of me that talks about justice feels that any way you can get facts into a trial that are relevant and comply with the rules, probably ought to be in the trial. If jurors have questions, well then they are going to have those questions in the jury room, so best to know before. It’s probably more valuable for the defense than the prosecutor.”

About the Author