THREE WAYS THIS MATTERS TO YOU

1. Your money: changes in the electric generation industry in Ohio mean Duke Energy and Dayton Power & Light Co. customers now have a choice of who supplies their electric, and can opt for suppliers with lower prices. Duke Energy, in the process of becoming a distribution and service only business here, and DP&L, still deliver power to homes and businesses.

For more information about choosing your electric supplier, go online to www.energychoice.ohio.gov.

2. Your health: New environmental rules are meant to reduce carbon pollution in the air, requiring more stringent emission controls for coal-fueled power plants. Natural gas-fired power plants still release emissions, but are considered cleaner than coal plants.

Area utility companies are closing some of the oldest coal-powered plants and are converting other coal-fired units to natural gas.

3. The economy: An abundant supply of natural gas running through the area is attracting development of new power plants, which can create construction and operations jobs.

CONTINUING COVERAGE

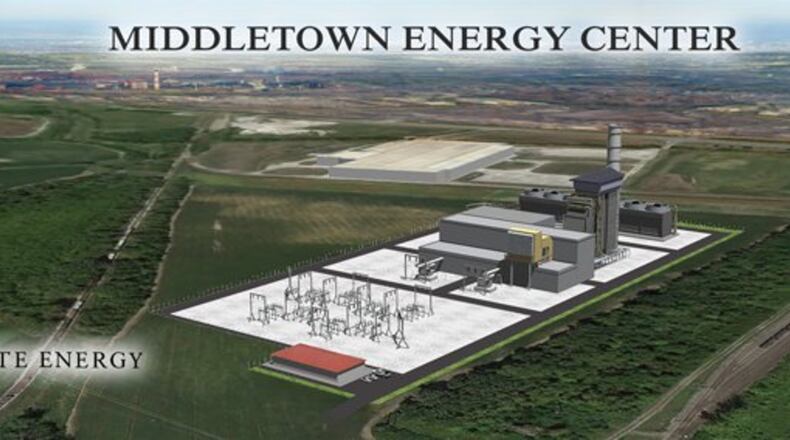

Since this newspaper was one of the first to report plans for a new power plant in Middletown, we have continued to provide news and information about the implications of building a natural gas-fired power plant here on the community.

Plans by a Florida company to build a natural-gas fired power plant in Middletown would make for the sixth power plant running in Butler County, the Journal-News has found.

Currently, electric utilities Duke Energy and the city of Hamilton operate peaking power plants in Butler County to generate electricity at the most in-demand times such as when temperatures dip below zero degrees and customers crank up the heat. Peaking plants, versus baseload plants, don’t operate year-round.

NTE Energy LLC of St. Augustine, Fla., publicly announced in January plans to build three power plants nationwide, including a $500 million natural gas plant in Middletown. The company must still obtain government permits and certifications. If everything moves forward, plans are to start construction midway through 2015 and open in 2018, producing more than 500 megawatts of electric power year-round.

NTE Energy’s power plant wouldn’t be the first in Butler County, nor is it the first natural-gas fueled plant. But there is a concentration of power plants in Butler County.

Similar to how southwest Ohio sits at the crossroads of two major highways — Interstates 70 and 75 — Butler and Warren counties sit at the crossroads of major natural gas pipelines, said Doug Childs, Hamilton public utilities director. The Rockies Express and Texas Eastern pipelines run underground through here.

“This is one of the best areas in the country for natural gas supply,” Childs said.

Access to natural gas and electric transmission lines were major factors in NTE Energy’s decision to locate here, as well as demand, said Mike Bradley, NTE Energy senior vice president of commercial services.

The market served by PJM Interconnection, the group managing the electric grid serving 13 states, including Ohio and Washington, D.C., is “a market with load growth,” Bradley said. “The region-wide economic recovery… kind of rolls into increased wholesale demand.”

To determine the locations and number of power plants operating in this corner of Ohio, this newspaper asked the environmental agencies that monitor the power plant emissions, Southwest Ohio Air Quality Agency in Cincinnati and Regional Air Pollution Control Agency in Dayton. The lists the agencies provided show as many as 26 power plants in Southwest Ohio, which was corresponded with utilities Duke Energy, Dayton Power & Light Co., and city of Hamilton.

The sites identified include five existing plants in Butler County.

Midwest Commercial Generation, Duke Energy’s commercial generation business, owns a natural gas-fired plant on Todhunter Road in Monroe that the company recently announced is for sale; Duke Energy Ohio and Kentucky owns a natural gas-fired plant on Woodsdale Road in Trenton; and Duke Energy Indiana owns a natural gas plant on Kennel Road in Madison Twp.

Hamilton local government, which owns its own electric, water and gas utility services, owns a power plant on North Third Street that burned coal until recently. Its burners were converted to all natural gas in 2013, Childs said. In a joint venture with American Municipal Power Inc., a cooperative of local governments, Hamilton also owns a natural gas plant on North Gilmore Road.

Two power plants on the list have closed: DP&L said it closed its coal-fired Hutchings Station in Miamisburg in 2013. Hutchings did not have federally mandated environmental controls and was removed from service, DP&L officials said. FirstEnergy Generation Corp. closed its Mad River coal plant in Springfield in 2010, and closed remaining natural-gas units at the same site in 2013, company officials said.

A coal plant co-owned by Midwest Commercial Generation, DP&L, and American Electric Power in New Richmond is set to close next year, the companies said.

Also two power plants on the list of 26 are at the same location. The W.C. Beckjord Station set to close in New Richmond has coal- and oil-burning units the companies list separately. Miami Fort Station in North Bend, also counted as two locations, burns coal and natural gas, according to the companies.

Deregulation

NTE Energy’s January announcement to enter the electric generation business in Ohio, and a second February announcement by Duke Energy to exit its commercial generation business, brings to light changing ownership of facilities.

Due to deregulation in Ohio, enacted by Ohio law, and effective in 2001, utility companies were required to separate their distribution and service business from their generation business, said Matt Schilling, spokesman for Public Utilities Commission of Ohio.

Local government utilities such as Hamilton are not under PUCO’s jurisdiction, and thus not affected by the law change.

Deregulation means commercial utility customers can now choose what company supplies or generates their electric, Schilling said. Customers do not choose who distributes their electricity. Local utilities Duke and DP&L still do that and respond to outages.

Prior to deregulation, a utility owned the generation plants, transmission wires and distribution. Utilities used to be guaranteed to get their costs back for operating power plants, costs that were sometimes passed on to customers, Schilling said.

By separating the generation business from the distribution business, it shifts the risk of investment in power plants from the rate payers to the plants’ private owners, Schilling said.

Auctions are held to supply electricity to the utilities. In the bidding process, no utility can buy 100 percent of the supply it needs from a single generator, he said.

“There’s now a competitive market for generation,” he said. The intent was “to create a competitive market that would hopefully drive prices down through competition.”

NTE Energy’s Bradley said deregulation had no bearing on their choice to develop a power plant in Middletown.

Meanwhile Duke Energy said on Feb. 17 its related company Midwest Commercial Generation is selling 13 power plants, including the one in Monroe, in part because the plants were earning lower revenues than the company hoped for.

Environmental rules

In 2011, a new U.S. Environmental Protection Agency rule was signed to reduce emissions of toxic air pollutants from all power plants, including those owned by private companies, utilities, cooperatives and municipalities. Power plant owners had four years to comply with the new emission standards for mercury, sulfur oxide and nitrogen oxide.

At the time the rule was introduced, approximately 40 percent of U.S. coal-fired power plants did not have the advanced emission controls required, according to the EPA’s estimates.

Meanwhile, a U.S. Supreme Court decision is due later this year on a case review, concerning whether the U.S. EPA exceeded its authority by issuing in 2011 a cross-state air pollution rule in 2011. At this time, the Clean Air Interstate Rule remains in place, according to the EPA.

At the end of 2013, the federal EPA proposed the first uniform national limits on the amount of carbon pollution that future power plants will be allowed to emit, the agency says.

As a result or rule changes, Midwest Commercial Generation, DP&L and American Electric Power plan to close Beckjord Station in New Richmond in early 2015.

“Beckjord is nearly 60 years old and the cost of installing emissions equipment would be far greater than the cost to do so on a newer plant. Furthermore, the coal-fired units at Beckjord are generally smaller and the site itself is constrained in terms of space, making the units more expensive to retrofit with controls,” said Sally Thelen, spokeswoman for Duke Energy, in an email. “The anticipated revenue from power sales would not justify the high costs associated with implementing upgraded controls at the facility — costs that would likely be borne by our customers.”

One misconception is that natural gas is a clean fuel, which is relative, said Brad Miller, assistant director of Southwest Ohio Air Quality Agency. It’s a cleaner fuel than coal, but “when you burn natural gas it still has emissions,” Miller said.

Sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxide are pollutants from burning coal that react in the atmosphere to form smog and soot, according to the EPA. When natural gas burns, it produces half as much carbon dioxide, less than a third as much nitrogen oxides, and one percent as much sulfur oxides as coal, according to the federal environmental agency.

About the Author