“One way or another, we’re going to pay for having unhealthy streams, because if you show me an area where the streams are not doing well, then I’m going to show you an area that has probably a lot of bank erosion problems, or possibly having to deal with going in and fixing roads that are washing out and people’s backyards eroding,” said hydrologist Mike Ekberg, manager for water resource monitoring and analysis at the Miami Conservancy District.

Credit: Nick Graham

Credit: Nick Graham

What’s contaminating the region’s surface water?

Increasingly, land use and the kinds of practices around streams and rivers are greatly impacting the physical habitat, Ekberg said. Natural buffers on the banks of rivers and other waterways, including trees, bushes and other vegetation that slow runoffs, have been removed, and farms and housing developments often come up to the channels. In addition, hard surfaces ― concrete, asphalt and roofs ― make it difficult for water to drain into the underground aquifer.

Without those buffers, rain water from farms and urban development runs into streams, rivers and lakes.

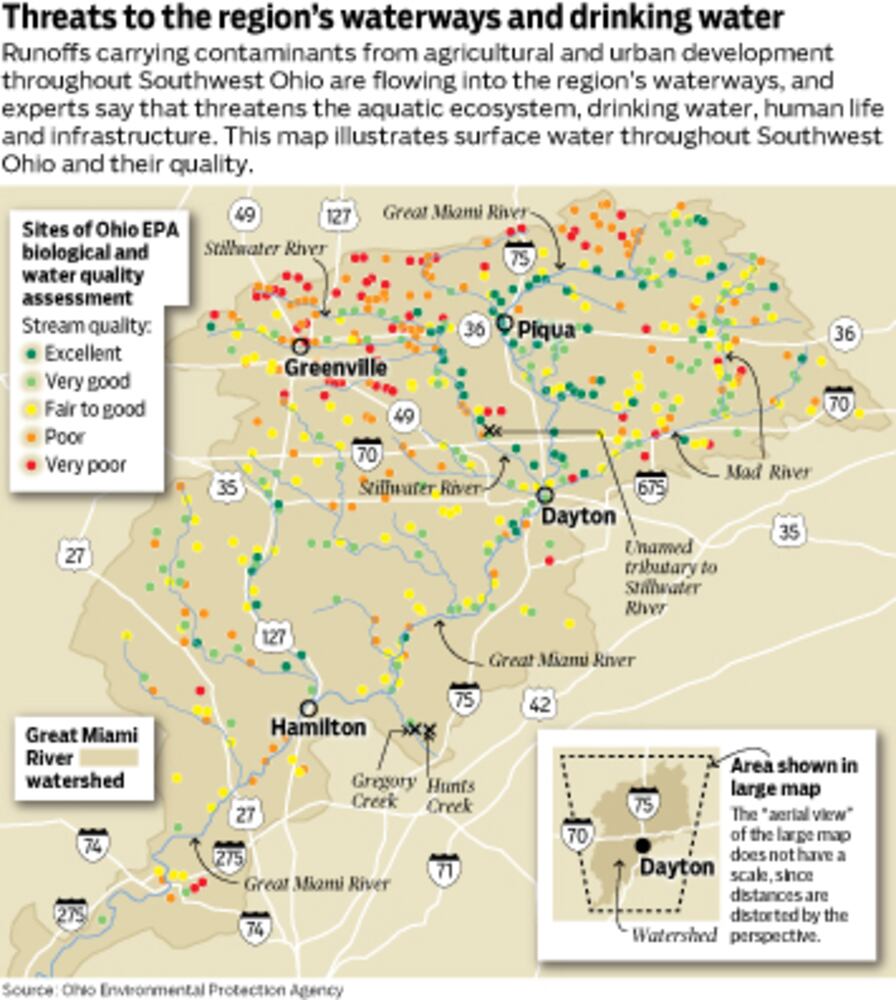

The pollutants in the area’s water include remnants of fuel products, building materials, fertilizers, manure, tar, pesticides and a potentially deadly group of chemicals called per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances ― or PFAS. Hundreds of streams throughout the region transport the runoffs to larger bodies of water such as the Great Miami River in the Dayton area and Gregory Creek in Butler County. The chemicals also seep into the Buried Valley Aquifer ― where the majority of communities in the region get their drinking water ― and travel as far as the Gulf of Mexico.

Meanwhile, streams take on much more water than they can handle, causing erosion, flooding and damage to private property and infrastructure.

The problem is not unique to Southwest Ohio. It is a nationwide issue that states and the federal government have been working to solve. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has developed programs and made funding available to states to reduce pollution. Ohio has also created programs.

How emerging contaminants are polluting surface and drinking water

Runoff, especially when there’s heavy rainfall, flows directly into local waterways. The many streams and creeks in the region drain a large part of the watershed and bring fertilizers, pesticides, pathogens and emerging contaminants from farms to the area’s larger surface water, said Abinash Agrawal, an earth and environmental sciences professor and groundwater remediation expert at Wright State University. In addition, animal waste from large hog or cattle farms can drain into nearby creeks.

That waste can contain pathogens, antibiotics and other pharmaceuticals given to the animals, all of which also travel to the surface water and eventually into the aquifer, Agrawal said.

In addition, rivers and other bodies of water throughout Southwest Ohio take on discharges from wastewater treatment plants. Certain micropollutants are not removed before the treated water is released in the rivers, Agrawal said, such as prescription drugs and hormones.

“They may be bad, but we don’t know the ramifications,” Agrawal said.

Perhaps the most polluted lake in the region

Grand Lake St. Marys, which stretches between Mercer and Auglaize counties, is perhaps the most polluted lake in the region. It’s in such bad shape that the Ohio Department of Natural Resources frequently issues notices asking people not to get in the water.

The lake is over-enriched with phosphorus and nitrogen because an excessive amount of fertilizers flow into it, Agrawal said. The supply of nutrients causes blue-green algae to grow excessively, which takes over the lake’s food chain. The algae then produces toxins that are harmful to aquatic creatures and humans. Excessive algae growth also depletes oxygen in the lake, causing fish and other creatures to die, he said.

In an attempt to treat the water, the Ohio Department of Natural Resources installed two wetland treatment “trains” to provide a natural way to slow down and filter nutrient-rich sediments from water before it reaches the lake, said Stephanie O’Grady, the agency’s spokeswoman. ODNR plans to add additional treatment trains in the near future, she said.

Erosion and crumbling infrastructure

Surface water such as the Stillwater River and Gregory Creek are healthy, Ekberg said. But they could deteriorate as nearby streams deposit excessive amounts of sediments in them. The sediments then travel through Indiana, Illinois, Kentucky and all the way down to the Gulf of Mexico, disrupting the ecosystem and impacting the fishing industry and communities along the way.

They also stand to damage infrastructure and private property. In Englewood, an unnamed stream that flows into the Stillwater River is causing erosion near that city’s wastewater treatment plant. The erosion started about six years ago, and it’s being affected by both climate change and human action, Ekberg said.

Several trees on its banks have either fallen or will soon fall, and much of the vegetation has washed away.

“We’ve had some intense rain events that have led to big flows going through here in this stream channel,” Ekberg said, pointing to the erosion about 3 feet from a chain link fence on the property, some of which the Miami Conservancy District owns. “The volume of water going through it was way higher than what the stream channel can carry. So what it’s trying to do is enlarge to accommodate the bigger volumes of water.”

Conservancy district officials know they have to take action to prevent the fence line from falling into the stream, but Ekberg said they’ve not ironed out the details.

Rapidly eroding streams exist throughout Southwest Ohio that threaten other infrastructure and private properties. For instance, at Trails of Four Bridges subdivision in Liberty Twp. in Butler County,, Hunts Creek, which flows into Gregory Creek, has caused erosion in various places in the community and surrounding neighborhoods. Some backyards and roads are on the verge of being sucked into the streams.

Financial impact of runoffs and contamination

The pollution and erosion is already affecting people’s pocketbooks, as the cost to treat public water supplies has increased because of emerging contaminants and infrastructure repair, said Chris O. Yoder, research director at the Columbus-based Midwest Biodiversity Institute. The cost will continue to rise to the tune of millions of dollars over time in each community, he and others say. In addition, quality of life will be disrupted if people aren’t able to fish, swim or boat if the lakes are contaminated.

But the answer is not to stop farming or building new communities. Instead, experts said better solutions are needed to prevent runoffs from polluting the water.

“The challenge is trying to find a balance between the need to protect a community’s supply of drinking water and not being a burden to economic activity,” Ekberg said. ”I think a community can serve both needs, but it requires some planning. The community needs to have an understanding of where its supply of drinking water comes from and where that supply is most vulnerable to contaminants from human activities. Those high vulnerability areas need to be protected.”

Possible solutions

Lane Osswald of Preble County is one of many farmers in the region who have taken steps to curb runoff and erosion. His family owns farms in Preble and Montgomery counties, and they do not till the land, he said. No-tilling keeps the soil firm to the ground, preventing it from washing away ― along with nutrients and other chemicals ― during heavy rain.

Another technique Osswald practices is cover crops, which is to grow a different crop when his main crops ― corn, soybeans and wheat ― are not planted. Growing something at all times slows erosion, improves the soil’s health, retains water and increases biodiversity. In addition, Osswald samples the soil every four years to ensure there’s not an excessive amount of nutrients, which are expensive and can wash away into local surface water.

“Based on that and which crops we’re going to be growing, we add no more nutrients than we need,” he said.

Credit: JIM NOELKER

Credit: JIM NOELKER

There’s no silver bullet to solving the pollution and erosion problem, so it will require multiple solutions, said Jordan Hoewischer, director of water quality and research at the Ohio Farm Bureau Federation. Educating the public as well as farmers is a major step, he and other experts said. The farm bureau has been working with farmers to help them find solutions and allowing them to understand the science and research behind new techniques and maybe tweaking old techniques, he said.

They’ve also appointed farmers to government programs such as H2Ohio, a comprehensive water quality initiative that Gov. Mike DeWine launched in 2019. Its purpose is to begin the long-term process of reducing phosphorus runoff from farms through the use of proven, science-based nutrient management best practices and the creation of phosphorus-filtering wetlands.

H2Ohio’s initial funding for the 2020-2021 two-year budget is $172 million, and it’s currently available to farmers in the northern part of the state. It’s not clear at this time when the program will be available to Southwest Ohio farmers.

Agriculture aside, the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency provides technical assistance to builders for issues related to controlling stormwater that might affect water quality, said Dina Pierce, an agency spokeswoman. The agency issues more than 2,000 general stormwater permits annually, she said.

Since 2003, applicants covered under Ohio EPA’s general stormwater construction permits are required to install and maintain best management practices to treat stormwater.

Other entities such as water conservancies and county and local organizations are more focused on managing stormwater for commercial and development purposes.

“These organizations are doing good work, but it’s also true that sometimes streambank erosion is a part of the stream naturally re-establishing its banks,” Pierce said.

About the Author