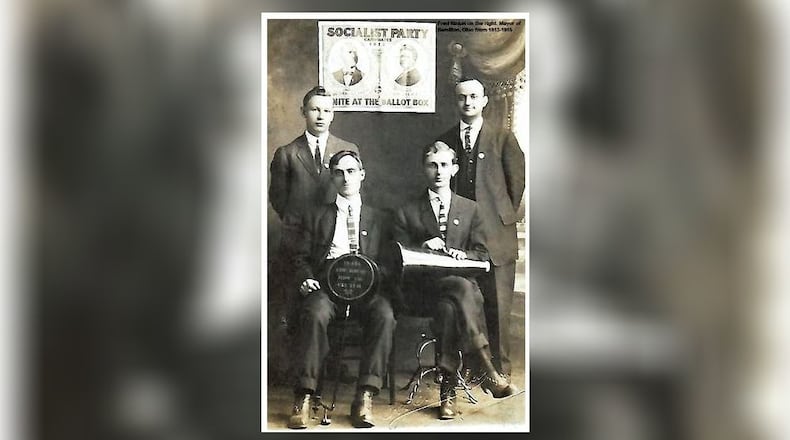

The Socialist mayor was lawyer Fred A. Hinkel. The party’s city councilmen were Frank J. Leisner, Charles J. Norris, Joseph B. Buckner, Charles Baker and Ferdinand Aker. B. F. Primmer was the new solicitor and Ernest Shafor was treasurer. William Blackall was elected clerk of the municipal court and Horace Shank was the first judge of the newly created municipal court.

Other elected officials were Joseph Vidourek, Democrat councilman; Charles W. Gath, Henry Welsh, and Chris Benninghofen, councilmen; Ernst E. Erb, auditor and Ernest G. Ruder, city council president, all candidates running on the Citizen’s Ticket. August W. Margedant, Harry G. Taylor and Louis Frechtling, the newly elected members of the school board were also Citizen’s Ticket nominees.

The winning Socialist Party majority exerted substantial influence over city operations because it was able to appoint patronage positions such as the city’s safety director, public service director, city engineer, building inspector, street commissioner and superintendents of the municipal gas, electric and water departments.

Impact of the 1913 flood

Election Day on Nov. 4, 1913 was fewer than eight months after the March 23-25 Great Miami River flood had devastated much of the Hamilton community. The city was still reeling from the deaths of several hundred people, thousands of others rendered homeless, hundreds of buildings destroyed, thousands of homes made unrepairable by the flood and the loss of hundreds of heads of livestock. Debris, mud, and contaminated water pools still dotted several areas within the city.

State law prohibited cities and counties from working across boundaries to solve large-scale problems, making the recovery from the flood a local government responsibility for each community. Just two months after the flood, more than 23,000 residents of Dayton had contributed $2,000,000 to design a flood protection system. General public opinion among many Hamilton residents was that the recovery efforts of the Democratic office holders were inadequate, too slow or misdirected.

The Socialist Party’s candidates were perceived to offer voters new leadership to better deal with the problems of recovering from the flood.

Local Socialist Party’s roots

The Socialist Party had been formed in 1901 by a merger of the Social Democratic Party of America which had been founded by Eugene V. Debs in 1898 and a splinter group of members of the Socialist Labor Party of America, the first socialist party, established in 1876. Locally, the party had offered voters candidates for several public offices as early as 1906 but they received very few votes. As an example, in the 1906 race for Common Pleas Court Judge, Clarence Murphy, Democrat, received 6,950 votes, Edgar Belden, Republican, won 6,795 votes and Daniel Hall, the Socialist candidate, won only 456 votes.

By the November 1911 election, however, the Socialist Party had substantially increased its clout in local politics. Socialists in Hamilton won a majority of seats on the nine-person city council, including two of three at-large seats (Charles A. Morris and Joseph B. Meyers) and three of the six ward seats (Lawrence Geis, Joseph Smith and Ferdinand Aker). Walter W. Hinkel, another socialist, was elected as president of council. Nationally, for the first time, the Socialist Party offered voters a full-slate of candidates in every state in the country.

On Nov. 6, 1911, the day before the election, Eugene V. Debs, nationally known socialist candidate for president in 1904 and 1908, exhorted a large crowd of voters to support the Socialist ticket and led a parade of more than a thousand people through Hamilton’s streets. Debs would also campaign for the presidency in 1912 and 1920 as the Socialist Party nominee.

The other elected officials in 1911 included Democrats winning positions as the city’s mayor (Thad Straub), solicitor (John F. Neilan), auditor (Henry A. Grimmer), treasurer (Walter Brown), and three councilmen (Chris Kaefer, Peter Weismann and Fred Holbrook) with one Republican (Henry Welsh) elected to the city council. The Socialists majority controlled the city council and organized it for the two year period from 1912 through 1913.

As might be expected, the split government brought about conflicts between the mayor and administration and the Socialist council majority during the 1912-1913 term. Socialist opposition killed several alternative plans for a proposed South Hamilton railroad crossing to improve safety because, as B. F. Primmer, the Socialist Party city solicitor said, “the crossing was not needed for rich men to run their automobiles over.” (Hamilton Evening Journal, Oct. 25, 1913, p. 2).

The November 1911 election also resulted in relatively wide-spread success for Socialist Party candidates across the country. In Ohio alone, Socialists were elected to serve as mayors in 12 other Ohio communities including Barberton, Canton, Conneaut, Cuyahoga Falls, Dillonvale, Fostoria, Lima, Loraine, Martin’s Ferry, Mt. Vernon, Salem and St. Mary’s. There were also Socialist Party candidates elected as city, township and county officials. According to a tabulation listed in the Cambridge University Press, socialists in 1912 held “some 1,200 public offices in 340 municipalities from coast to coast, among them 79 mayors in 24 states.”

Local results of the November 1913 election produced a city government made up of 10 elected Socialists, five Citizen’s Ticket candidates and one Democrat councilman. Early in 1914, the Socialist majority on Council adopted controversial ordinances reducing the size of the police force by 33%, cutting the number of patrolmen from 36 to 24 and eliminated two detectives and one sergeant as cost-saving measures. It also established monthly police salaries for the police chief at $115 ($1380 per year or $42,475 in 2023), detectives at $85 ($1020 yearly or $31,400), and patrolmen at $70 ($840 per year or $25,850 in 2023). The Socialist majority had passed the same police staff reduction measure in 1913, but Mayor Straub had vetoed it.

Social control problems

During the early 1910s, Hamilton was known as a “wide open town” where vagrancy, gambling, prostitution and alcohol was quite common. While the recovery from the Great Miami River flood dominated local activities, the Socialists in office were also expected to deal with the issues the Hamilton Republican-News called “social control” problems. The newspaper wrote that the Socialists “have refused to state what stand they would take towards the elimination of the red light district, gambling, and Sunday theaters.”

The Nov. 2, 1915 municipal election brought the Socialist Party’s control of City Hall to an emphatic end. According to the Hamilton Daily Republican-News, the city’s voters “repudiated Hinkelism in a manner which left no doubt as to their disapproval of the present administration” and returned the Democratic Party to dominance. Democrats were elected to serve as mayor, president of council, auditor, treasurer, solicitor and eight city council seats. Only one socialist was returned to a seat on council.

The new city government included John A. Holzberger, mayor; Leon Ziliox, president of council; Ernst Erb, auditor; Charles Kehm, treasurer; and Harry Koehler, solicitor. The eight Democratic councilman elected were Dan Baker, Chris Benninghofen, Henry Brinker, Charles Gath, Joseph Vidourek, George Grathwohl, James Cahill and George Renners. Robert Sohngen and John Burnett were elected to the Board of Education. Ferd Aker, socialist, was reelected to serve on council.

An editorial in the Hamilton Journal-News proclaimed that “Socialism has been on trial for two years and it has failed.” The feeling was fairly widespread. There were no socialists successfully elected to any Butler County posts during the Nov. 7, 1916 general election. Democratic candidates received majority votes for U. S. President, Ohio Governor, U. S. House of Representatives, U. S. Senator, and all county offices, state representatives, and judicial positions. Clearly, socialism as a political influence in Hamilton and Butler County was over.

About the Author