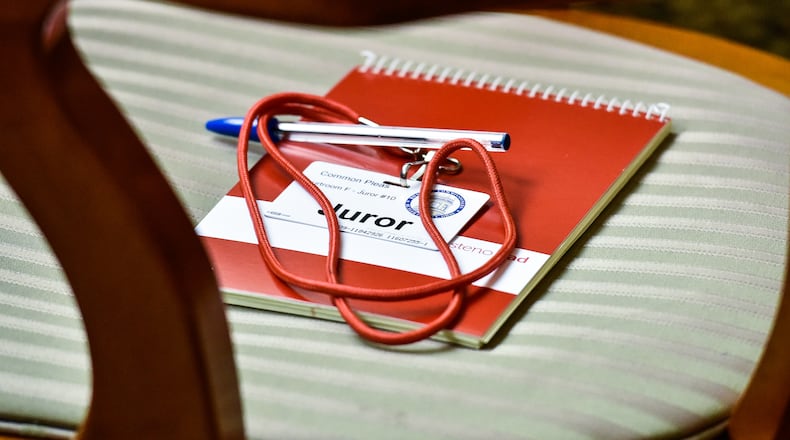

In one Warren County Common Pleas courtroom, jurors are not only provided notebooks, but permitted to ask questions of witnesses — a rarity in the state.

Jury note-taking is the norm locally, and has been the case in the memories of attorneys who have practiced for 20 years or more.

Recently, Butler County Visiting Common Pleas Judge Daniel Hogan did not permit note-taking after a jury was seated for former auditor Roger Reynolds’ trial. Hogan began the standard preliminary procedure guidelines for the jury and did not address note-taking.

Hogan told a juror who asked if they could take notes that he was on the side of no note-taking and looked to the prosecution and defense to argue otherwise. They did not.

Credit: Nick Graham

Credit: Nick Graham

Hogan declined comment about his note-taking practice until after the February sentencing of Reynolds.

Judge Jennifer McElfresh, Butler County common pleas judge for nine years and a longtime county assistant prosecutor, said she does not recall any trial where note-taking was not permitted for a jury.

“I have not practiced in any courts where they have not been able to take notes and I do permit them to take notes. But it is really up to the discretion of the trial court, the supreme court has ruled in several cases,” she said.

McElfresh and other judges typically address the practice straight from the law based on Ohio jury instruction guidelines.

“It does say that for some time note-taking by jurors were not permitted. There was some concern originally that it would distract the jurors attention from what was actually going on in the courtroom,” McElfresh said.

There is also another theory that some believe it is not helpful because a juror’s notes would be perceived to be more important than a juror’s memory, she said.

Others are of the belief that notes help with recall, especially in a complicated case. She is one of them.

“It is important that you remind (jurors) it is for the recall of that particular juror and should be used as a memory aid not treated as a verbatim record of the testimony,” McElfresh said.

Juror notebooks are under the watch of the court during trial. They are not something a juror can put in their purse or pocket to review at home or on lunch break. They have an identifying marker specific to each juror and they collected and redistributed before and after court.

Notebooks are permitted in the room during deliberations, then collected and shredded when the trial in over, which is part of standard jury instruction.

“I am a note-taker myself,” McElfresh said. “For me it depends on how you learn. Some people are better at just listening and seeing. I like to accommodate both kinds of learning so the jurors can make the best decision.”

Butler County Common Pleas Judges Keith Spaeth, Greg Howard and Dan Haughey all permit note-taking during jury trials. All say they too are note takers and feel the jurors as triers of the facts should have the same opportunity.

Spaeth said judicial practices are often what the custom is in the county where the judge was elected and began their law career.

“But we do warn people, you can get so caught up in taking meticulous notes that you are not observing their body language, their demeanor and trying to get a real good handle on are there any (signs) that this person isn’t telling the truth,” Spaeth said.

Note-taking is also not required, and judges say some opt not to jot down anything in the spiral notebooks.

“Some take very few or none at all. Then others are asking the bailiff for a second notebook,” Spaeth said.

Warren County Common Pleas Judge Donald Oda II changed his policy about jury note-taking in the past few years after serving on a three-judge panel in a capital murder case.

“Judge Peeler, Judge Kirby and I listened to the testimony, deliberated and reached a verdict. All three of us were taking notes, as most judges do, the entire time and I found these notes were helpful to us when we were deliberating. It made our discussions about the case much more productive,” Oda said.

“Allowing jurors to take notes improves the deliberation process and with better deliberation, hopefully, you will get better verdicts,” Oda said.

Jurors may sometimes ask questions

Warren County Common Pleas Judge Time Tepe is one of the few in the region who also permits jurors ask questions of witnesses within the parameters of the law. Oda said that is not a practice he plans to adopt.

“Although I have seen from Judge Tepe that it does produce good questions from the jurors, I am more concerned about the impact than not asking a question that a juror submits — asking about prior convictions or hearsay testimony, for example. If I am asking some of the jurors’ questions, but not all of them—– I worry that this may play a role in how the jurors evaluate the case. I also do not ask questions in a jury trial. I let the attorneys handle all the questioning,” Oda said.

In Tepe’s courtroom, after a witness testifies, the bailiff passes out cards to jurors who can then write a question for that witness. Questions are not required and the cards are not signed. After the questions are collected, both sides confer with the judge. Then Tepe reads the jury questions that he ruled were appropriate.

For now, Tepe is the only area judge letting the jury have a more vested role in the process with questioning. A 2020 survey by the Ohio Jury Management Association indicated only 26 out of 95 judges responding permitted jurors to ask questions of witnesses.

Tepe, who was elected and took the bench in 2017 after practicing law for 31 years, began considering the practice several years into his judgeship. After hearing the idea from a judge in northern Ohio, Tepe adopted the policy in the fall of 2019.

He plans to continue the practice and his philosophy is give the jury the tools needed to make a decision.

Tepe said as a practicing attorney he did encounter judges who did not permit note-taking.

“I just don’t like to limit jurors,” Tepe said. “My philosophy is we need to make it easier on the jury any way we can. Let’s give them the information they need to make a just decision.”

He added permitting jurors to ask questions is part of that philosophy.

“I know that sometimes attorneys don’t like it “ Tepe said. “And people are confused by it because attorneys always get a chance before the question is read to object. Just like any question that is asked of a witness, the judge is the one who decides what questions are appropriate.”

It is a matter of getting to the truth, Tepe said.

“The attorneys may be trying to go around certain questions. I have found that jurors ask really good questions,” Tepe said. “My goal is to get a fair trial to both sides. You want a jury to make a just decision, and my goal is to help them come to that conclusion. They are the triers of the facts, so why not give them as much information and the tools they need to do that?”

CRIME & SAFETY REPORTS

Lauren Pack has been a courts and crime reporter for nearly 30 years in Butler County and the region, covering hundreds of criminal cases and a trials in Butler, Warren and Preble counties. Sign up for more from her through our Crime & Safety Report weekly email newsletter. journal-news.com

About the Author