The situation was particularly dangerous because the site sits above the Great Miami Aquifer, a giant source of groundwater that holds 1.5 trillion gallons of water serves the needs of 3 million consumers for drinking water.

But officials in this region are on alert for chemical spills that could taint the water source.

Spills from Chem-Dyne killed more than a million fish and water animals in the river, Ohio officials said when they sued Chem-Dyne and other companies. Fires there during the 1970s worried the community, and in September of 1976, Ohio officials sued, with then-Gov. Richard F. Celeste and Attorney General Anthony J. Celebrezze Jr. announcing the legal action.

A 1982 federal-court settlement involving the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency ordered cleanup by the site’s operators and also payments by companies that had sent chemicals to the Hamilton location. The removal of soil and later cleansing of the property — by pumping water from around the land, removing chemicals and returning water below-ground — has continued for decades, and monitoring continues, under that court settlement.

From 1987 through 2010, some 35,020 volatile organic compounds were removed, according to state regulators, at a cost of more than $30 million.

This media outlet published an article Sunday about efforts to prevent such pollution and clean up environmental spills to protect the aquifer.

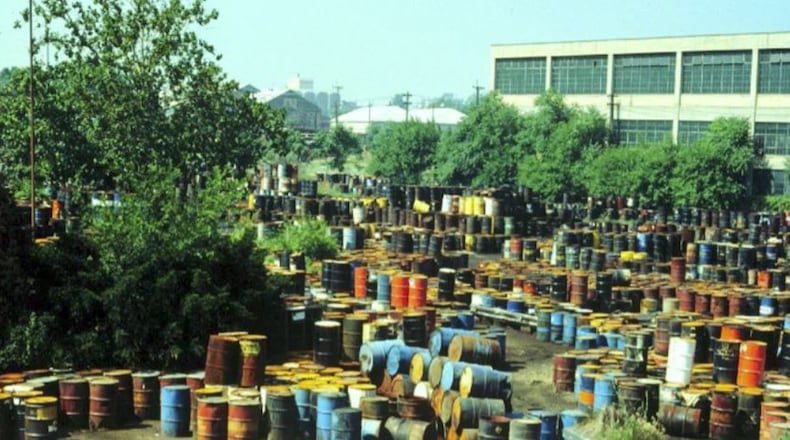

Chemicals at the site included pesticides, chlorinated hydrocarbons, solvents, waste oils, plastics, resins, PCBs, acids and caustics, heavy metal and cyanide sludges. Workers at the site often mixed liquid wastes in open pits, releasing noxious vapors, according to a U.S. Environmental Protection Agency report from the time. “Reportedly, 55-gallon drums were punctured with pickaxes and allowed to leak or were dumped into the ground or into a trough or pit,” while tank cars reportedly were emptied into the ground, as well as troughs and sewers, according to the same reports.

“We’re happy they’ve reduced an enormous amount of contamination,” said Tim McLelland, manager of the Hamilton-to-New-Baltimore-Area Ground Water Consortium. “Obviously, it’s not still all cleaned up, so it’s on our radar.”

John Bui, who manages Hamilton’s drinking-water-processing operations, said the contamination has never threatened the city’s well fields. It “has been contained on that site, and it’s been monitored there,” Bui said.

Unthreatened by the chemicals are the city’s water wells that are north of the former Chem-Dyne property, as are wells the city and Fairfield uses to the south, which mostly are in Fairfield.

Hamilton won a gold medal for best municipal tap water in the world at 2010 and 2015 tasting competitions in Berkeley Springs, W.Va. Late last month, the water won a silver medal at the same competition, for second-best in the nation.

About the Author