Howard’s mother ran the family home at 53 Chestnut St. and ensured that her children attended Sunday School at the Payne A.M.E. Church every weekend. His father did “odd jobs” for a living, according to the census and also worked as a cook. He also served in city government, under the pre-charter ward system, as a representative for the Second Ward and was a member of the Elks.

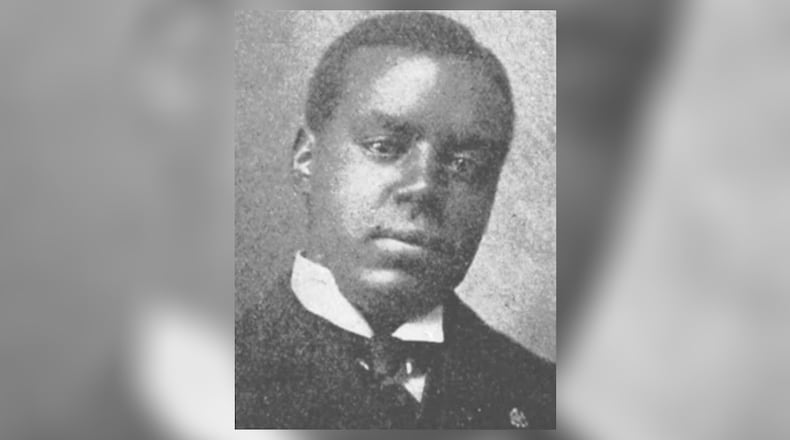

Even back to his teenage years, Howard was known for his strong oratory and writing skills and deep intellect. He graduated from Hamilton High School in the Class of 1900, becoming the first Black high school graduate in the city’s history, and was selected by his peers to deliver an address at their commencement.

Howard was accepted to Howard University, a historically Black university in Washington, D.C., and attended the Howard School of Law. Completing law school, Howard passed the bar in Ohio, making him the youngest Black lawyer in the state and the first and only Black lawyer in Butler County.

Howard married Elizabeth L. (Wells) Howard, a schoolteacher from Texas, on July 10, 1907. He brought her back to Hamilton where they lived with Howard’s parents. Rachel Howard died of heart disease in 1909.

Howard had initially started his practice in Dayton, but returned to Hamilton in 1904 and opened a law office at 116 High Street, now the site of the Butler County Administrative Center. Divorce suits accounted for the vast majority of the cases he handled early in his career, though he soon also took on criminal cases as well, mostly representing Black plaintiffs and defendants.

In his first criminal case, Howard defended Joe Richardson on an assault charge. Richardson had gotten into a fight with Will Hogans while ice skating and slashed Hogans’ forehead with a knife.

Howard won the case and Richardson off on a self-defense plea after proving that Hogans had been the aggressor in the altercation. In reporting the victory, the Hamilton Evening Democrat commented, “Thomas Howard gives promise to becoming quite a successful attorney. He conducted his case well.”

Along with his usual divorce cases, Howard took on several other criminal cases. In 1912 he unsuccessfully attempted to defend Frank Smith from a robbery charge, and despite losing the case, the newspaper once again noted, “the fine argument made on behalf of Smith by attorney Thomas J. Howard doubtlessly was in his favor and kept the jury from reaching an agreement sooner.”

During his time in Hamilton, Howard gave several speeches on behalf of local politicians, political organizations, and community groups. He also joined his father as a member of the local Elks Club.

In 1913, Howard relocated his family and law practice to Cincinnati. In Cincinnati, he became a member of the Allen Temple A.M.E. Church and joined the Elks and Masons of that city. A lifelong Republican, Howard became involved with local politics in Cincinnati, serving as a ward representative.

He had a major victory in 1919, when he was able to get Frank Burton acquitted on a pick pocketing charge. It was the first acquittal by a jury in the new Hamilton County Courthouse.

The following year, Howard’s arguments lead to an acquittal of John Sanders on a murder charge, stemming from a body found in a shack in Elmwood Place. The jury returned the non-guilty verdict in 20 minutes, finding there to be a lack of evidence to convict Sanders.

However, two of the hardest lost cases in Howard’s career followed, both of which involved Black defendants who were 17 years old at the time they committed their crimes. Both defendants were facing the death penalty.

Howard, with co-council James G. Steward, attempted to defend John Coverson, who had shot and killed a plain clothed Cincinnati police officer on May 14, 1927. Although the Enquirer noted that Howard made a “strong case for mercy” his death sentence was upheld. Coverson was executed in the electric chair on Jan. 9, 1928.

On Oct. 8, 1932 a bank was robbed in Silverton and a cashier was shot to death. Joseph “Buddha” Murphy and his brother James were convicted of the crime in separate trials, with Howard and his co-council Edward M. Ballard represented Joseph Murphy. Although Howard and Ballard’s efforts were successful in getting a 30 day reprieve, based on eye witness testimony, ultimately both Murphy brothers were executed in the electric chair on Aug. 14, 1933.

Howard’s father died in the midst of the latter case on Feb. 14, 1933. Howard himself would only live for two more years, dying relatively young at age 51.

Howard was admitted to General Hospital in Cincinnati, now University Hospital, for hypertensive heart disease on Feb. 26, 1936. He died at the hospital 6 days later on Mar. 3, 1936.

Howard was interred in Greenwood Cemetery. The Cincinnati Bar Association recognized Howard as part of a memorial service held the following year.

Brad Spurlock is the manager of the Smith Library of Regional History and Cummins Local History Room, Lane Libraries. A certified archivist, Brad has over a decade of experience working with local history, maintaining archival collections and collaborating on community history projects.

About the Author