In Hamilton, Schwab learned the barrel making trade, working as a cooper in his formative years. He married Caroline (Young) Schwab, a young woman from a fellow Bavarian family whose name was anglicized from Yung, on Jan. 13, 1859.

Many biographies of Schwab, including his obituary, claim that he continued working as a cooper until becoming engaged in a commission merchant business with Henry Schlosser, a prominent local brewer and maltster, and James Fitton in Cincinnati in 1866. Although these men were likely partnered in a business enterprise, newspaper evidence suggests they were most likely involved in the distilling business and whiskey trade.

Schwab operated a whiskey warehouse in 1866 and in 1867 was put on trial for attempting to defraud the federal government by bribing a revenue collector. He was later acquitted, but it wasn’t the only time in his career that he was accused of bribery.

Along with the warehouse operation, Schwab may also have been connected with an oil company and a race track in Cincinnati in the mid-1860s, though the details of these business endeavors are not verified. However he had acquired it, by 1866, at age 28, he had amassed a fortune.

The Cincinnati Commercial described his rise to prominence, “from limited circumstances, through honesty, industry, and a streak of good luck, he is now one of the largest taxpayers in the county.” That same year, Schwab erected Hamilton’s Dixon-Globe Opera House, now known as the Robinson-Schwenn Building.

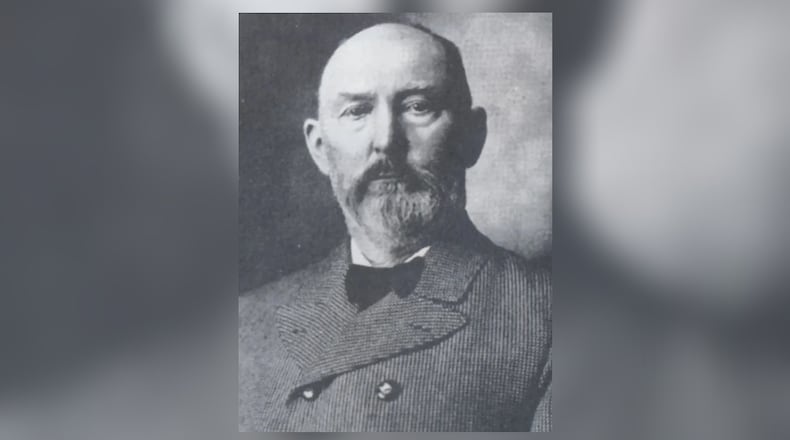

Credit: Nick Graham

Credit: Nick Graham

Likely as a result of the case, Schwab pulled out of Cincinnati in 1868 and invested in a brewery operation in Hamilton with two new partners, Herman Reutti and the venerable Ferdinand VanDerveer, a former sheriff, local war hero, and future judge. Known as Peter Schwab & Company, the company purchased the brewery originally built by local brewing pioneer John W. Sohn, who had introduced German lager to Hamilton.

Lager had taken the city by storm, quickly becoming Hamilton’s favorite beer and shutting down all other competition, especially as German immigrants continued flocking to the city. However, the brewery struggled from the start and Schwab left the company, which became Reutti & VanDerveer, around 1870.

Likely missing the wealth he had previously enjoyed, Schwab immediately went back into the whiskey business, purchasing the Miami Distillery. The Miami Distillery, located on the present site of Matandy Steel, had been intermittently operated by a string of owners since around 1858, selling its signature “Fairfield Bourbon.”

Schwab operated the distillery and warehouse until 1874. Unsubstantiated claims were made by bitter political rival, Thomas McGehean, that Schwab was violating liquor laws by illegally selling untaxed whiskey and had also paid off government inspectors.

He further claimed Schwab was attempting to start a “Whiskey Ring” with other regional breweries to jointly illegally sell their whiskey beyond what was allowed within government regulations. McGehean, who had made a plethora of other political enemies in addition to Schwab, was murdered in Hamilton in 1875. No one was ever tried for his murder.

Possibly in light of the accusations, or for some other reason lost to history, Schwab divested of the distillery in 1874 and bought out Reutti & VanDerveer. Now with total control over the brewery, he renamed it the Empire Brewery and set about transforming it.

At first little profit was made, but that soon changed, as did the name of the company. Cincinnati Brewing Company was incorporated by Schwab in 1882 with a capital of $250,000.

Schwab focused heavily on marketing, labeling his lager “Pure Gold” and advertising it as “The Beer that Made Milwaukee Jealous.” He also directly challenged competitors, in one instance taking Pure Gold to Indianapolis and selling it for $3 less than its local breweries.

By 1903, Schwab’s company was brewing 120,000 barrels and selling 82,000 barrels per year to markets stretching from St. Louis to Washington, D.C. The company expanded with increased space for brewing, an artificial ice plant, and a bottling plant, eventually taking up an entire city block at the northwest corner of Monument Avenue and Sycamore Street.

As the beer poured out, the money poured in, allowing Schwab to exercise a huge amount of influence over local politics. He represented the Second Ward on the city school board, had seats on the city sewer commission and the board of Mercy Hospital, sponsored former Ohio Governor James E. Campbell in an unsuccessful bid for a presidential candidacy nomination, and was a powerhouse in the local Democratic party.

Caroline Schwab had died in 1881, and Schwab remarried in 1888, taking Mary Elizabeth (Niederman) Schwenn as his bride. Mary, the widow of John Schwenn, had five children that now became step siblings to Schwab’s seven children from his first marriage.

“Uncle Peter” died after an extended illness on Sep. 13, 1913. A three-page obituary was published in the Democratic leaning Hamilton Evening Journal two days later.

Cincinnati Brewing Company was taken over by his son, Peter E. Schwab, and continued being hugely profitable until being shut down by the start of Prohibition in 1919.

Brad Spurlock is the manager of the Smith Library of Regional History and Cummins Local History Room, Lane Libraries. A certified archivist, Brad has over a decade of experience working with local history, maintaining archival collections and collaborating on community history projects.

About the Author